Are Oats Healthy?

You know how we say that grains exist on a spectrum of suitability, from “really bad” wheat to “not so terrible” rice? Well, what about the rest of ‘em? They may be the most commonly consumed (and thus encountered) grains, but wheat and rice aren’t the only grains on the spectrum. Since I get a lot of email about oats, I figured they were a good choice for this post. Besides – though I was (and still mostly am) content to toss the lot of them on the “do not eat” pile, I think we’re better served by more nuanced positions regarding grains. Hence, my rice post. Hence, my post on traditionally prepared grains. And hence, today’s post on oats. Not everyone can avoid all grains at all times, and not everyone wants to avoid all grains at all times. For those situations, it makes sense to have a game plan, a way to “rank” foods.

You know how we say that grains exist on a spectrum of suitability, from “really bad” wheat to “not so terrible” rice? Well, what about the rest of ‘em? They may be the most commonly consumed (and thus encountered) grains, but wheat and rice aren’t the only grains on the spectrum. Since I get a lot of email about oats, I figured they were a good choice for this post. Besides – though I was (and still mostly am) content to toss the lot of them on the “do not eat” pile, I think we’re better served by more nuanced positions regarding grains. Hence, my rice post. Hence, my post on traditionally prepared grains. And hence, today’s post on oats. Not everyone can avoid all grains at all times, and not everyone wants to avoid all grains at all times. For those situations, it makes sense to have a game plan, a way to “rank” foods.

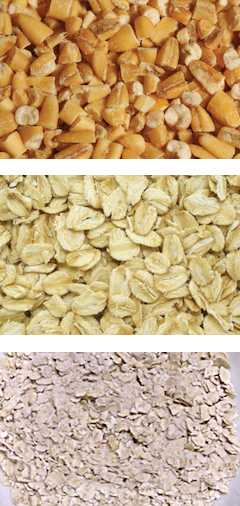

Today, we’ll go over the various incarnations of the oat, along with any potential nutritional upsides or downsides. But first, what is an oat?

The common oat is a cereal grain, the seed of a species of grass called Avena sativa. Its ancient ancestor, Avena sterilis, was native to the Fertile Crescent in the Near East, but domesticated oats do best in cool, moist climates like regions of Europe and the United States. They first appeared in Swiss caves dated to the Bronze Age, and they remain a staple food crop in Scotland. The “whole grain” form of an oat is called a groat (the picture up above depicts whole oat groats) and is rarely sold as-is, except maybe as horse feed. Instead, they’re sold either as steel-cut, rolled, or instant oats.

Steel-cut oats are whole groats chopped into several pieces. Some of the bran flakes off, but some is retained. Steel-cut oats take longer to cook, contain the most nutrients (and antinutrients like phytic acid), and taste nuttier than conventional oats.

Steel-cut oats are whole groats chopped into several pieces. Some of the bran flakes off, but some is retained. Steel-cut oats take longer to cook, contain the most nutrients (and antinutrients like phytic acid), and taste nuttier than conventional oats.

Rolled oats are steamed groats that have literally been rolled out and flattened, with the bran discarded. When most people think of “oats,” they’re thinking of rolled oats.

Instant oats are rolled, steamed, and precooked oats. They’re essentially the same as rolled oats, only often accompanied by sugary flavorings and rendered immediately edible by the addition of hot liquid.

The main problems with oats are the phytic acid and the avenin, a protein in the prolamine family (along with gluten from wheat, rye, and barley, and zein, from corn). As far as phytic acid (or phytate) goes, oats contain less than corn and brown rice but about the same amount as wheat. As you know from previous posts, phytate has the tendency to bind minerals and prevent their absorption. So, even if a grain is rich in minerals, the presence of phytate prevents their full absorption. Ingestion is not absorption, remember. As I understand it, you can, however, reduce or eliminate phytate by lactic fermentation. I’m not sure the degree to which phytate can be deactivated, but one study does show that consuming oats that underwent lactic fermentation resulted in increased iron absorption rather than reduced. Another source claims that simple soaking isn’t enough, since oats contain no phytase, which breaks down phytate. Instead, you’d have to incorporate a phytase-containing flour to do the work; a couple tablespoons of buckwheat appear to be an effective choice for that. Combining both lactic acid bacteria (whey, kefir, or yogurt), companion flour (buckwheat), water, and a warm room should take care of most of the phytate… but that’s a lot of work!

Avenin appears to have some of the same problems as gluten in certain sensitive individuals, although it doesn’t appear as if the problem is widespread or as serious. Kids with celiac disease produced oat avenin antibodies at a higher rate than kids without celiac, but neither group was on a gluten-free diet. When you put celiacs on a gluten-free diet, they don’t appear to show higher levels of avenin antibodies. It looks like once you remove gluten, other, potentially damaging proteins become far less dangerous. One study did find that some celiacs “failed” an oats challenge. Celiac patients ate certified gluten-free oats (quick note: oats are often cross-contaminated with gluten, so if you’re going to experiment with oats, make sure they’re certified gluten-free), and several showed signs of intestinal permeability, with one patient suffering all-out villous atrophy, or breakdown of the intestinal villi. A few out of nineteen patients doesn’t sound too bad, but it shows that there’s a potential for cross-reactivity.

Why do oats get so much praise from health organizations, particularly from the American Heart Association (whose coat of arms boxes of Quaker Oats proudly display)?

Well, oats contain a specific type of soluble fiber called beta-glucan that increases bile acid excretion. As bile acid is excreted, so too is any serum cholesterol that’s bound up in the bile. The effect is a significant reduction in serum cholesterol. In rats with a genetic defect in the LDL receptor gene – their ability to clear LDL from the blood is severely hampered – there’s some evidence that oat bran is protective against atherosclerosis. Of course, the very same type of LDL-receptor-defective mice get similar protection from a diet high in yellow and green vegetables, so it’s not as if oat bran is a magical substance. Like other prebiotic fibers, oat bran also increases butyrate production (in pigs, at least), which is a beneficial short-chain fatty acid produced by fermentation of fibers by gut flora with a host of nice effects. Overall, I think these studies show that soluble fiber that comes in food form is a good thing to have, but I’m not sure they show that said fiber needs to come from oats.

Oats also appear to have a decent nutrient profile, although one wonders how bioavailable those minerals are without proper processing. A 100 gram serving of oats contains:

- 389 calories

- 16.9 grams protein

- 66 grams carbohydrate

- 10.6 grams fiber (with just under half soluble)

- 7 grams fat (about half PUFA and half MUFA)

- 4.72 mg iron

- 177 mg magnesium

- 3.97 mg zinc

- 0.6 mg copper

- 4.9 mg manganese

Oatmeal is a perfect example of the essentially tasteless, but oddly comforting food that’s difficult to give up (judging from all the emails I get). It’s tough to explain, because it’s not like oatmeal is particularly delicious. It’s bland, unless you really dress it up. No, I suspect it’s more than taste. I myself have fond childhood memories of big warm bowls of oat porridge steaming on the breakfast table. I’d add brown sugar, dig in, and head out to adventure through blustery New England mornings with a brick of pulverized oats in my happy belly. The nostalgia persists today, even though I don’t eat the stuff and have no real desire to do so. Heck, seeing Wilfred Brimley’s diabetes awareness TV spots still makes me think of those bowls of oatmeal and all the playing they fueled. Maybe it’s a combination of nostalgia and physical satiation?

Still, since I had some steel-cut oats laying around the house from a past houseguest who absolutely needed his oats, I decided to give them a shot. To self-experiment. To – gasp! – willingly and deliberately eat some whole grains. McCann’s Irish oats, they were. Raw, not steamed, and of presumably high quality. I’d been researching this post, and I came across an interesting thread on Paleohacks in which a recipe for baked oatmeal was described. Go ahead and check it out. I followed it exactly, soaking the oats in an acidic medium (Greek yogurt) and adding the buckwheat flour, which I made a special trip to the store for. When it was done cooking, I added a bunch of blueberries and some grass-fed butter, a touch of salt and a few shakes of cinnamon, and the Paleohacks poster was right: it did make the kitchen smell great. I sat down to eat my bowl. I’d been on a long hike that morning and I had done some heavy lifting as it baked, so I felt like I was as ready as I’d ever be.

It was… okay. The liberal amount of butter I added quickly disappeared without a trace, and I had to stop myself from adding more because that would have been the rest of the stick. The berries and cinnamon looked and smelled great, but they were swallowed by the blandness. I even added a tablespoon of honey but couldn’t taste it. It was satisfying in the sense that it provided bulk in my stomach. A half hour after, I felt kinda off. It’s hard to describe. A spacey, detached feeling? Slightly drugged? However you want to describe it, it didn’t feel right. Only lasted half an hour or so, though. My digestion was fine (hat tip to Jack Kronk and his Paleohacks recipe for getting that part right), and I never felt bloated besides the initial “brick in the stomach” feeling.

That’s my take on oats. Better than wheat, worse (and more work to improve) than rice. I won’t be eating them because I frankly don’t enjoy them, there are numerous other food options that are superior to oats, and I don’t dig the weird headspace they gave me, but I’ll admit that they aren’t as bad as wheat. If I want starch, I’ll go for some sweet potatoes.

No comments:

Post a Comment