by RYAN ANDREWS

Resistant starch is a type of starch that isn’t fully broken down and absorbed, but rather turned into short-chain fatty acids by intestinal bacteria. This may lead to some unique health benefits. To get the most from resistant starch, choose whole, unprocessed sources of carbohydrate such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and beans/legumes.

What makes a starch “resistant”?

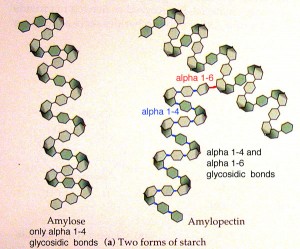

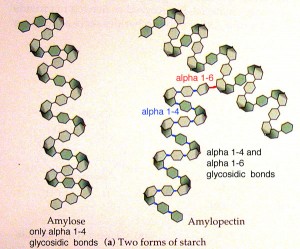

All starches are composed of two types of polysaccharides: amylose and amylopectin.

Amylopectin is highly branched, leaving more surface area available for digestion. It’s broken down quickly, which means it produces a larger rise in blood sugar (glucose) and subsequently, a large rise in insulin.

Amylose is a straight chain, which limits the amount of surface area exposed for digestion. This predominates in RS. Foods high in amylose are digested more slowly. They’re less likely to spike blood glucose or insulin.

Thus, resistant starch is so named because it

resists digestion.

While most starches are broken down by enzymes in our small intestine into sugar, which is then absorbed into the blood, we can’t fully absorb all kinds of starch.

Some starch — known as resistant starch (RS) — isn’t fully absorbed in the small intestine. Instead, RS makes its way to the large intestine (colon), where intestinal bacteria ferment it.

RS is similar to fibre, although nutrition labels rarely take RS into account.

SCFAs and RS

However, RS still plays an important role in our diets even though we don’t necessarily absorb it.

When RS is fermented in the large intestine, short chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate, along with gases are produced. SCFAs can be absorbed into the body from the colon or stay put and be used by colonic bacteria for energy.

Evidence suggests that SCFAs may benefit us in many ways. For instance, they:

- stimulate blood flow to the colon

- increase nutrient circulation

- inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria

- help us absorb minerals

- help prevent us from absorbing toxic/carcinogenic compounds

The amount of SCFAs we have in our colon is related to the amount and type of carbohydrate we consume. And if we eat plenty of RS, we have plenty of SCFAs.

Rate of digestion changes absorption

RS can also help us stay lean and healthy.

As we cover in a

Research Review on processed vs. whole foods, researchers found that less-processed foods offered less energy than refined foods. In other words, although whole and processed foods may contain the same amount of calories, we

absorb fewer calories of energy from whole foods.

Since RS is incompletely digested, we only extract about 2 calories of energy per gram (versus about 4 calories per gram from other starches). That means 100 grams of resistant starch is actually only worth 200 calories, while 100 grams of other starch gives us 400 calories. High-RS foods fill you up, without filling you out.

The way we’ve modified/processed grains and starchy vegetables in the modern food supply diminishes the amount of RS we consume (think: cereal bars instead of oats, burgers instead of beans, potato chips instead of boiled potatoes). And fibre sources such as wheat bran, psyllium, and methyl-cellulose (Citrucel) don’t have the same benefits.

Thus, to get the most benefits from RS, we need to consume it in whole food format.

Most developed countries (including Europe, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia), which have a highly processed diet, consume about 3-9 grams of RS per day. In developing countries, diets are often based around whole plant foods and the intake of RS tends to be around 30-40 grams per day.

Potential benefits of RS

IMPROVED BLOOD FATS

RS may help to lower blood cholesterol and fats, while also decreasing the production of new fat cells (the latter has only been shown in rats). Also, since SCFAs can inhibit the breakdown of carbohydrates in the liver, RS can increase the amount of fat we utilize for energy.

BETTER SATIETY

RS can help us feel full. SCFAs can trigger the release of hormones that reduce the drive to eat (leptin, peptide YY, glucagon like peptide). After someone starts eating more RS, it may take up to one year for gut hormones to adapt.

RS slows the amount of nutrients released into the bloodstream, which keeps appetite stable.

BETTER INSULIN SENSITIVITY

RS doesn’t digest into blood sugar, which means our bodies don’t release much insulin in response.

RS might also improve insulin sensitivity via alterations in fatty acid flux between muscle and fat cells. Some data indicate that ghrelin might increase with RS consumption, improving insulin sensitivity (this is counterintuitive since ghrelin drives appetite). RS may also lower blood fats (see above), which also improves insulin sensitivity.

IMPROVED DIGESTION

RS may help alleviate irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, constipation, and ulcerative colitis. RS can add bulk and water to the stool, aiding in regular bowel movements.

SCFAs can help to prevent the development of abnormal bacterial cells in the colon and enhance mineral absorption (especially calcium).

BETTER BODY COMPOSITION

Since RS has less energy (calories) per gram than other starches, it can help us eat less. And consuming more RS may have a thermic effect in the body.

KEEPING US HYDRATED

For those receiving treatment for cholera and/or diarrhea, RS can assist in the rehydration process (since it can normalize bowel function).

IMPROVED IMMUNITY

Consuming RS can influence the production of immune cells and inflammatory compounds in the gut.

Where is RS found?

RS is found in starchy plant foods such as:

- beans/legumes

- starchy fruits and vegetables (such as bananas)

- whole grains

- some types of cooked then cooled foods (such as potatoes and rice)

The longer and hotter a starch is cooked, the less RS it tends to have — except for Type 3 RS.

| Types of resistant starch |

|---|

| Type 1: Physically inaccessible | Type 2: Resistant granules |

| Cannot be broken down by digestive enzymes.Found in: legumes, whole and partially milled grains, seeds. | Intrinsically resistant to digestion and contains high amounts of amylose.Found in: fruits, potatoes, hi-maize RS products, corn, some legumes.

Note: the more “raw” or “uncooked” a food is, the more RS it tends to have, since heat results in gelatinization of starch – making it more accessible to digestion. Type 3 starch is the exception to this rule.

|

| Type 3: Retrograded | Type 4: Chemically modified |

| When certain starch-rich foods are cooked and then cooled, the starch changes form, making it more resistant to digestion.Found in: cooked/cooled foods like potatoes, bread, rice, cornflakes. | Companies have isolated RS (usually from corn) to include it in processed foods (e.g., breads, crackers, etc.).This is not naturally occurring RS — it’s produced mostly via chemical modification, and it’s found in synthetic and commercialized RS products, such as “Hi-Maize Resistant Starch”. |

How much RS should we consume?

Data indicates that RS is safe and well tolerated up to about 40-45 grams per day. Consuming more than this might result in diarrhea and bloating, since high amounts can overwhelm the fermenting ability of our colonic bacteria.

How we respond to RS varies by the type. One might notice more side effects when consuming RS3 (versus RS1, RS2, RS4). Our ability to ferment RS can increase over time, making it possible to adapt to a higher RS intake.

RS seems to be tolerated best when:

- It’s in solid food form (rather than liquid)

- It’s consumed as part of a mixed meal (rather than alone)

- Consumption is increased gradually over time (rather than a lot at once)

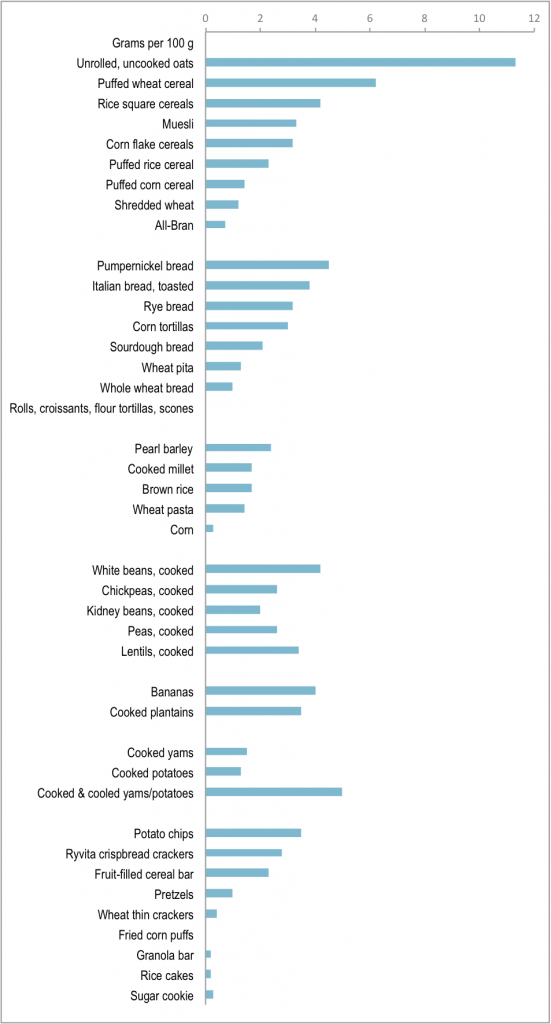

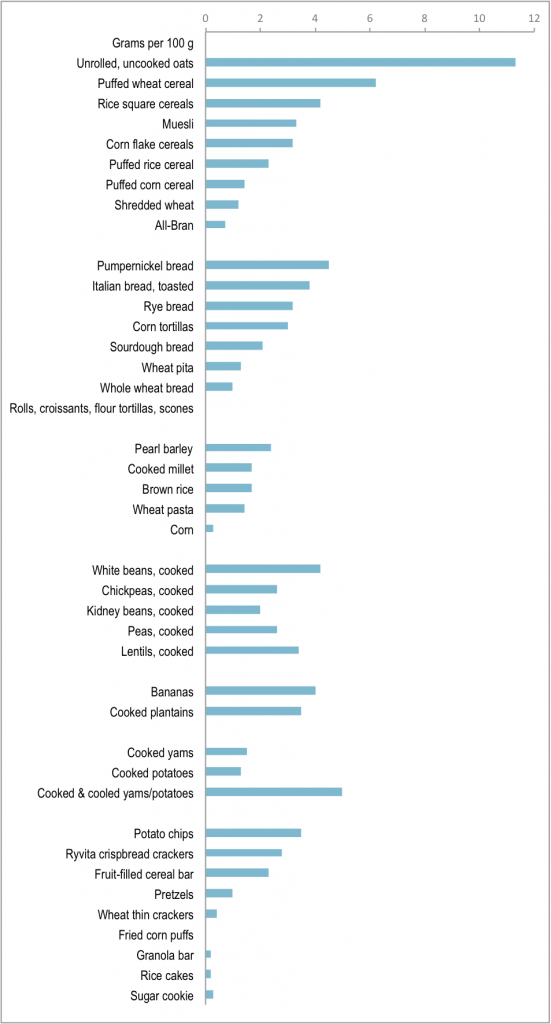

Here’s an idea how much RS is found in food. Note: these are average values and will vary.

Grams of RS per 100 g of food

Summary and recommendations

We absorb more energy (calories) from cooked and highly refined and processed carbohydrate dense foods. If we let machines and ovens do the digestion for us, we are left with highly digestible starches. Not good for glucose control, staying lean, or intestinal health.

Various cultures thrive and stay lean when eating whole unprocessed legumes, intact grains and starchy vegetables. RS may be one factor that enables this.

We might see some benefits from as little as 6-12 grams/day of RS, but closer to 20 grams/day might be ideal. This is easy to get if you eat plenty of whole plant foods.

More than 40 grams/day might cause digestive problems — especially if this RS comes from industrially produced RS products. In any case, we probably don’t get the same benefits of RS if it’s processed (i.e. an industrially created RS product) as we do from whole foods.

References

Anderson GH, et al. Relation between estimates of cornstarch digestibility by the Englyst in vitro method and glycemic response, subjective appetite, and short-term food intake in young men. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:932-939.

Nilsson AC, et al. Including indigestible carbohydrates in the evening meal of healthy subjects improves glucose tolerance, lowers inflammatory markers, and increases satiety after a subsequent standardized breakfast. J Nutr 2008;138:732-739.

Johnston KL, et al. Resistant starch improves insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome. Diabet Med 2010;27:391-397.

Bodinham CL, et al. Acute ingestion of resistant starch reduces food intake in healthy adults. Br J Nutr 2010;103:917-922.

Grabitske HA & Slavin JL. Gastrointestinal effects of low-digestible carbohydrates. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2009;49:327-360.

Robertson MD, et al. Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:559-567.

Higgins JA, et al. Resistant starch consumption promotes lipid oxidation. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2004;1:8-19.

Wolever TM, Spadafora P, Eshuis H. Interaction between colonic acetate and propionate in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:681-687.

Higgins JA. Resistant starch: metabolic effects and potential health benefits. J AOAC Int 2004;87:761-768.

Landin K, et al. Guar gum improves insulin sensitivity, blood lipids, blood pressure, and fibrinolysis in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;56:1061-1065.

Weickert MO, et al. Cereal fiber improves whole-body insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese women. Diabetes Care 2006;29:775-780.

Maki KC & Raines TM. Dietary fibers, insulin sensitivity, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Scan’s Pulse 2011;30:6-9.

Nugent AP. Health properties of resistant starch. British Nutrition Foundation Nutrition Bulletin 2005;30:27-54.

Position of the American Dietetic Association: Health implications of dietary fiber. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:1716-1731.

Elmstahl HL. Resistant starch content in a selection of starchy foods on the Swedish market. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002;56:500-505.

Murphy MM, et al. Resistant starch intakes in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:67-78.

Feder D. The Skinny Carbs Diet. Rodale. 2010.

Grams of RS per 100 g of food

Grams of RS per 100 g of food