Aerobic training gets a bad rap.

Aerobic training gets a bad rap.However, I would argue that aerobic training isn’t what you think it is, either.

Today we’re going to focus on long duratio. The term Joel Jamieson uses in his Ultimate MMA Conditioning manual for this type of training is cardiac ouptut, or CO for short.

CO isn’t the only way to train the aerobic energy system, but it is a powerful one and has numerous benefits.

Increased ATP Production

If you’ve ever taken a basic physiology course, you know that energy production all comes down to ATP. ATP is the “fuel” our muscles use to contract, so without it, we’re pretty much worthless.

We have three energy systems in our body:

ATP-PCr,

Anaerobic (glycolytic), and

Aerobic.

Now here’s the cool thing; all of these systems have very unique pros and cons.

The ATP-PCr system is the fastest at producing energy, as it only takes one step.

The downside? The ATP-PCr system can only fuel your body for 6-10 seconds. BOO.

The aerobic system is at the opposite end of the spectrum. The aerobic system is the slowest at producing energy, but it’s really freaking efficient when it gets going and cranks out 36 ATP’s every time through the cycle.

The other cool benefit of the aerobic energy system is that you can lean on it for hours upon end to produce energy for you.

In between the ATP-PCr and aerobic systems is the anaerobic, or glycolytic, system. This system boasts a lot of the cool stuff like fast energy production (ala the ATP-PCr system), but it doesn’t have the capacity to do so for an extended period of time.

The other down side is that high-intensity anaerobic training is downright brutal, both from a mental and physical perspective.

Here’s the bottom line — if you want to be able to do things for an extended period of time, you need a strong and healthy aerobic system.

Improved Recovery

It’s obvious that the aerobic energy system is the big dog if you want or need to produce energy for a long period of time.

But I think that’s already well known. What most people don’t realize is that a robust aerobic energy system can help you recover more quickly from both intense bouts of exercise, as well as between training sessions.

While you’re going to be tapped into your sympathetic nervous system while you’re training, that shouldn’t be activated and turned on all the time. Doing so will hinder recover and affect your ability to sleep.

Heart Efficiency

Now we’re getting into the nitty gritty details that are specific to CO type training.

Remember CO stands for cardiac output, so the heart is a primary focus of this training. Smarter people than myself would say you’re chasing a central adaptation (i.e. heart) versus a more peripheral adaptation (i.e. in the muscles, enzymes, capillarization, etc.).

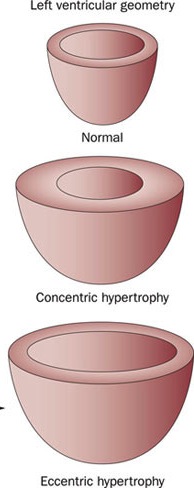

When you do low intensity work (often noted as 120-150 beats per minute), you allow a maximal amount of blood to profuse into the left ventricle of your heart.

When you do low intensity work (often noted as 120-150 beats per minute), you allow a maximal amount of blood to profuse into the left ventricle of your heart.As you force blood into that left ventricle, it’s in there just long enough to stretch the heart walls. Over time this creates an adaptation – quite simply your left ventricle stretches and gets bigger/wider.

When you stretch that heart wall, you can get more blood in and out with each heartbeat. The technical/geeky term for this is stroke volume, or the amount of blood you’re moving with each beat.

All this makes your heart more efficient. If you can move more blood with each heartbeat, your heart doesn’t have to beat as fast.

So cardiac output training increases stroke volume and decreases resting heart rate.

Cool huh?

Doing high-intensity exercise has a slightly different effect on the heart. Instead of the heart getting bigger and wider, the heart wall actually gets thicker.

Think about this – if your heart is beating fast, all it’s trying to do is get blood in and get it back out as quickly and forcefully as it can.

So the adaptations on your heart are quite different between high intensity and low intensity exercise. And this adaptation has much more far-reaching effects than just the heart.

Read on.

Shifting the Autonomic Nervous System

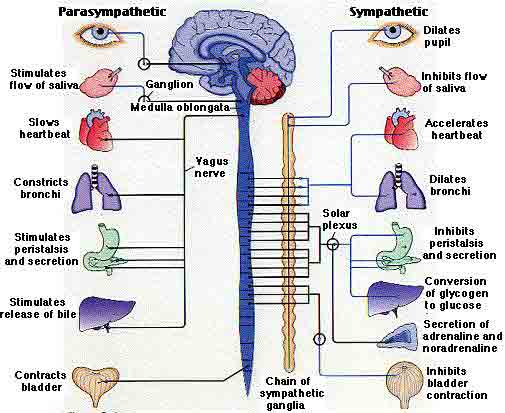

One of the big things we assess with our clients and athletes is whether they are parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system dominant.

For a super-quick primer, here are some things to remember:

For a super-quick primer, here are some things to remember:Sympathetic – Toned up, anxious, fight or flight, etc.

Parasympathetic – Chilled out, relaxed, rest and digest, etc.

One of the easiest ways to determine whether someone is parasympathetic or sympathetic dominant (along with their heart adaptations) is to check their resting heart rate.

If someone is consistently above 60 beats per minute, they tend to be more sympathetic dominant. As you can imagine, the higher their resting heart rate, the more sympathetic they are.

If someone is consistently below 60 beats per minute, they tend to be more parasympathetic dominant.

CO style training can help decrease sympathetic drive, which helps you chill out and relax. I’ve had numerous clients and athletes who, after incorporating CO workouts into their programming for a handful of weeks, comment on how they’re more relaxed and sleeping better as a result.

Recovery Between Bouts

Every good athlete will have times when they are going hard for an extended period of time and go glycolytic.

This isn’t a problem – in fact, it’s going to happen at some point in time.

The question is, once you go glycolytic can you get out of it?

Too often if an athlete has poor aerobic development, they will go hard one or two times during a game and then never shift out of glycolysis.

Which explains why they fatigue and gas out!

A well developed aerobic energy system will not only keep you out of anaerobic metabolism longer, but it will also get you back into your aerobic system faster following periods of high intensity (anaerobic) exercise.

The Knock on Long Slow Duration

Do you remember that scene in 8-Mile, where Eminem basically destroys his nemesis by calling himself out in a rap battle?

He left his opposition with nothing to say, and that’s my goal here.

I know what you’re probably thinking, so let’s get out with it right here:

“Long duration, low intensity cardio makes you slow”

So let’s say you have the fastest, strongest and most explosive athlete on the planet, and you have them start doing some cardiac output work to improve their work capacity and recovery.

I hate to tell you this, but you don’t just spontaneously become super slow.

You don’t think about continuous training and morph into a marathon runner who looks and performs like one, big slow-twitch muscle fiber.

Remember, the adaptations you create in your body are based on ALL of the training you’re doing, not just one medium.

If you’re running fast, jumping high, and lifting heavy things in your current program, all of these things will help offset and mitigate some of the perceived drawbacks to CO-style training.

Here’s another cool thing – once you get your ticker in better condition, you don’t have to continue to do this stuff forever!

The key is to maintain that adaptation – come back to CO-style training from time-to-time, but by all means use more high-intensity methods of aerobic training to preserve those gains.

“It’s not sport-specific”

First and foremost, I’d ask you to define what “sport” you play.

Most team sports (soccer, basketball, volleyball, football, etc.) are incredibly reliant on the aerobic energy system. If you go onto Pubmed and do some poking around with regards to time-motion analysis, you’ll come to the same conclusion.

Here’s the issue:

If you simply watch a sport and watch the ball the whole time, it looks helter skelter – people are running around like chickens with their heads cut off.

If you simply watch a sport and watch the ball the whole time, it looks helter skelter – people are running around like chickens with their heads cut off.But you can’t watch the ball – you have to watch the player.

Sure, there are certain players that are running around like chickens with their heads cut off, but most are going through bouts of high intensity movement, interspersed with times of low-intensity cruising or flat-out standing around.

If you’re the science type, check out some of these studies that I think will only help support my cause further:

Repeated Sprint Ability #1

Repeated Sprint Ability #2

Aerobic Endurance Training

There’s obviously a ton more out there, but those are a good starting point.

Building a kick-ass aerobic energy system is definitely “sport-specific,” even if it’s not always high-intensity. Just remember that if you have a poorly developed aerobic base, CO training is a great tool to help re-build your foundation.

But that’s another bone I have to pick. I’m going to let you in on a clue here:

You don’t have to train “sport-specific” year round! And in that same vein, not everything has to be high-intensity.

In fact with my professional athletes, I’ll actually ease them back into their off-season workouts with lower intensity exercise whenever possible.

Consider this: A professional soccer season is 9 or 10 months long. At best, I may have a 6-8 week off-season before they head back off to camp.

The NBA isn’t much better – depending on when the team finishes up, you may only get 10-12 weeks in the off-season.

But before I get them in the gym, they will probably take 2-3 weeks of down time to rest and heal up from the season.

Not only does low-intensity exercise offset the chance that they will get injured when they get back to training, but it also helps re-build a foundation that they might have lost during that time off!

Quite simply, I know that the bigger and more stable their aerobic foundation is going into a season, the more resilient they’ll be. I love this quote from Charlie Weingroff:

“Increased aerobic capacity leads to improved tolerance to all biomotor abilities.”

Quite simply, we need a better balance between high intensity and low intensity work.

“Glycolytic training improves aerobic development”

I’m not totally sure how this has gotten so out of control, but I’ll do my best to challenge it head on.

Let me be blunt:

Aerobic training is in direct competition to anaerobic training.

Aerobic training is in direct competition to anaerobic training.The adaptations are totally different.

Different adaptations to the heart.

Different adaptations to the enzymes your body produces.

Different adaptations to your mitochondria.

Again, I can’t stress this highly enough, the adaptations are totally different.

One of the biggest issues could be in the research, especially with untrained individuals. With an untrained individual, I can throw everything at them all at once and they will improve.

I could literally have them on a powerlifting routine M-W-F, with cross country running on T-Th-Sa and they would probably improve in both strength and conditioning.

But if I did that for any extended period of time their gains would plateau. As a client or athlete develops, you have to become more and more specific with your programming, and focus on one or two non-competing foci for each program.

Now I know what some of you are thinking – “But Mike – what about the Tabata study? They improved aerobic capacity with anaerobic training.”

Which is true – but if you read the entire study, you’ll also realize the high intensity group also did one day of low-intensity, steady state training as well. In this case, the Tabata group did 30-minutes of steady state cycling at 70% of VO2 max every week.

Furthermore, they did 10 minutes of low intensity cycling as a warm-up every day prior to their Tabata session, for a total of 70 minutes of low intensity work every week.

Confounds the study just a little bit, right?

So hopefully I’ve convinced you that their are numerous benefits to CO training, and that more times than not they outweigh the negatives.

Now let’s look at how we determine if someone is a good candidate for CO training, as well as exploring training options.

The Assessment Process

At IFAST, we look at numerous tests to determine how efficient your body is. Three of our keystone tests are:

Resting heart rate,

One-minute go test, and

A Modified Cooper’s Test.

Between these three tests we can determine the efficiency of an athletes heart, his heart rate recovery, and predict his anaerobic threshold.

If your goal is to determine if someone needs low intensity, long duration work (from know on known as cardiac output, or CO), resting heart rate may be your best bet.

Our goal for most clients and athletes is to get their resting heart rate under 60 beats per minute. It may sound simple, but I consistently see even well conditioned (i.e. lean) athletes rolling in with resting heart rates in the high 60′s and even the upper 70′s.

When a client or athlete has a high resting heart rate, I can assume that they are sympathetic dominant (constantly fight or flight). This will not only impact their recovery between exercises and sets, but also between workouts as well.

Furthermore, I know they probably don’t sleep well, either, which further compromises recovery.

So when this athlete walks in, I know that CO training will be one tool in my toolbox to help them.

How to Train Cardiac Output

Now that we’re getting into the nitty gritty info here, let me make one thing imminently clear:

Cardiac output is NOT the only method of developing the aerobic energy system.

As I mentioned before, Joel Jamieson references eight different methods of aerobic training in Ultimate MMA Conditioning.*

EIGHT!

Cardiac output is one of those, and we use it when and if it’s necessary. Again, if someone is in poor cardiovascular condition (resting HR above 60) we’ll use CO as one means to help re-build their aerobic system

(*If you’re reading this blog and you don’t have a copy of Joel’s book, please pick up a copy right away. It’s in my Top 5 training books of all time — it’s that good.)

Implementing Cardiac Output

When it comes to cardiac output development, the standard exercise prescription looks something like this:

120 or 130 beats per minute, working for anywhere from 30-90 minutes.

Now the next question invariably becomes, “what should I do?”

As my good friend Eric Oetter likes to say, “the heart is a dumb muscle.”

Therefore, it doesn’t really matter all that much what you do for that time, as long as you’re in that target heart rate zone.

Meatheads like to do stuff like drag sleds, push the Prowler, or some combination of a bunch of different exercises and mobility drills.

Athletes could use this for low-level technical work. Dave Tenney has his soccer players go out and dribble to get their touches in.

A basketball player could get some court-work in – footwork, ball handling, working on specific moves, etc.

The key is to keep your heart rate in that 120/130-150 beats per minute range and you’re good to go.

Who Will Benefit From This?

The most obvious example of someone who will benefit from this type of training is an athlete who gasses out quickly when performing their sport.

If they have a poor aerobic base, quite simply, not only will they not be able to go for long periods of time, but their ability to recovery from high-intensity bouts of exercise will be compromised as well.

But athletes who play aerobic dominant sports such as football, basketball and soccer are the obvious examples. I have a more broad answer:

I think most of us would benefit from some cardiac output work.

Think about it — everything we do nowadays is go, go, go.

We go into the gym and get after it.

We stay up too late and don’t sleep enough.

Our commutes, our jobs, and even our personal lives cause us inordinate amounts of stress.

And all of this leads to chronic over activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress response.

Two of the best things we can do for our health and livelihood on a daily basis is take 10 full, deep breaths every day and do some low-intensity exercise a couple times a week.

Trust me, if you drop your resting heart rate 15-20 beats per minute, I have no doubt you will look and feel markedly better.

No More HIIT Training?

Before I wrap up this magnum opus, let’s open one last Pandora’s box:

Mike – are you saying that we don’t ever need to do high-intensity training?

That’s not what I’m saying at all. There are times and places where high-intensity training is absolutely warranted.

If your only goal is fat loss, high-intensity intervals are a sure-fire way to expedite this process. However, I could make the argument that some of these clients are so far out of shape that if we truly care about their livelihood, it makes more sense from a physiological perspective to get them an aerobic foundation and base first.

High-intensity intervals combined with longer rest intervals will also help develop the aerobic energy system. I can’t stress this enough – CO is just one type of aerobic training! There are numerous methods out there that are explosive in nature. The biggest thing you need to manipulate are the work-to-rest ratios.

If you participate in a sport that is highly anaerobic in nature (such as wrestling, MMA, etc.) you need to dedicate the last portion of your training to developing the glycolytic energy system. Just remember that if you have a big aerobic base, you can build a bigger glycolytic engine on top of it AND recover faster from those intense bouts of exercise.

If you read the Joel’s work, or even reference the Tabata study, it leads us to believe that the bulk of your adaptations in the glycolytic energy system occur in the first 4-6 weeks of training, with 8 weeks being on the outer limits.

So if that’s the case, why are we constantly pushing the limits? Sure it’s fast, but is it creating the adaptation that we want for ourselves?

Our clients?

Our athletes?

Maybe it would be smarter to take a step back so we can take 3-4 steps forward in the future.

Summary

Whether your goal is to become a dominant athlete or just move and feel better, I think cardiac output training has a place in most people’s programs.

It’s not as sexy, intense or hardcore as high-intensity interval training, but the benefits are numerous and wide-ranging.

If your goals include moving and feeling better, recovering faster, and/or having less stress and anxiety, CO training may be the missing piece of the puzzle.

All the best

MR

No comments:

Post a Comment